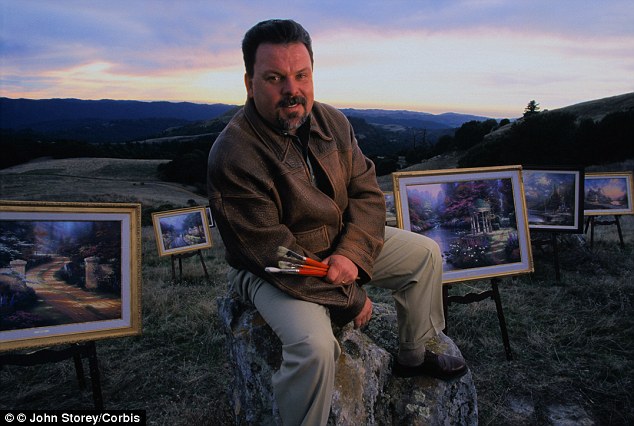

LOS GATOS, CALIFORNIA, 6 April — Thomas Kinkade, “The Painter of Light” died today of unknown, and apparently natural causes at his home in Los Gatos, CA. He reportedly sold over 10 million works in the United States and was hanging in 1 in 20 American homes. Loved by the public, scorned by critics, Kinkade was the Bouguereau of our time.

Like William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825 – 1905) a century before him, Kinkade created romantic fantasies that gave the people what they wanted. An uncomplicated, warm, organic world predominated by love and joy.

I am truly sad at the death of this all-too-young human being, two-years younger than Steve Jobs was, and, ahem, a mere 12 years older than I am today. I’m sorry Kinkade didn’t enjoy a longer life, although the career and success and family life he had in his 54 years was remarkable. I’m sorry for the loss, for all of us, for his friends and loved ones, and for the millions who treasured his romantic vision.

This isn’t really the day for critiques, still, since it’s likely the only time I’ll ever write about Kinkade I have to admit that I find his work troubling. For me it comes down to Romanticism vs Realism, and as a virtual performance artist, it’s a little strange that I would call his work too romantic!

It is more than a little crazy that someone who does virtual performance art would critique Kinkade’s romanticism. Even though my own work is necessarily romanticism, not gritty realism, I hope I do strive for truth in my fiction. For a “real” honesty in my virtual world of pixels. At least for myself, our “pretend” avatars do at times reach a gritty, painful truth of life.

At the end of Man of La Mancha, Dale Wasserman’s Cervantes character says,

Maddest of all, to see life as it is and not as it should be.

The speech of which that is the concluding line is a manifesto for romanticism. Still, for me, “To see life as it should be” is not to see it as the simple fantasy of an idyllic, pastoral, Kinkade home in the woods. It is “true” that many people yearn for this vision, they buy Kinkade paintings and prints and it speaks a sort of “truth” to their dreams. But it is the truth of the iPad. Kinkade’s little houses and Jobs’ sexy appliances have a bit in common: both are perfect, fetishistically desirable, and so perfectly defined that they offer no room for the rough edges of humanity. Both are utopias of a sort, there are no creepy guys in trench coats near Kinkade homes, and Jobs regularly rejected even humorous and harmless iPad apps if he thought they had any potential to upset a chunk of his customer base. Kinkade world and Jobs world are both perfect. They are both utopias. But they are somebody else’s utopia, and we fit in only if we Stepford Wifeicize our beings to meet the requirements of the landscape. And that for me is a dystopia, not a utopia. A nightmare, not a dream.